The impact of secondhand smoke

In 1986, the U.S. surgeon general concluded that secondhand smoke was a major health risk to nonsmokers. In 2014, the surgeon general estimated that secondhand smoke causes the premature death of 41,000 adults and more than 400 infants each year. Secondhand smoke is classified as a Group A carcinogen, a substance known to cause cancer in humans and animals.

What is Secondhand Smoke?

Secondhand smoke is a mixture of smoke released by the burning end of cigarettes, pipes or cigars, and smoke exhaled from smokers, which can be involuntarily inhaled by nonsmokers. It contains more than 7,000 chemical compounds, 69 of which are known to be carcinogenic to humans or animals.

Here are some known carcinogens found in secondhand smoke:

- arsenic (used in pesticides)

- lead (formerly found in paint)

- polonium-210 (a radioactive element)

- formaldehyde (used to embalm the dead)

- benzene (a gasoline additive)

Patterns of Secondhand Smoke Exposure

Adults and youth are exposed to secondhand smoke in places ranging from homes and vehicles to public indoor and outdoor spaces.

YOUTH

- An estimated 98.3 percent of youth who live with a smoker have been exposed to secondhand smoke. In contrast, only 39.9 percent of youth who did not live with a smoker were exposed.

- Almost half of middle and high school students (44.5 percent) are exposed to secondhand smoke from cigarettes. Nearly 25 percent (24.2 percent) are exposed to secondhand aerosol smoke from e-cigarettes. While less toxic than smoke from cigarettes, e-cigarettes emit many potentially toxic substances and research is still being gathered on the harmfulness of exposure.

- Although secondhand smoke exposure among youth with asthma declined between 2005 and 2010, the majority were still exposed, with higher exposure among low-income youth. More than 1 in 6 youth with asthma were exposed to in-home secondhand smoke.

- Nearly 15 percent (14.7 percent) of middle and high school students who have never used tobacco are exposed to secondhand smoke inside a vehicle. More than 15 percent (15.5 percent) are exposed at home and 35.2 percent are exposed in outdoor or indoor public areas.

SMOKE-FREE HOMES

- In addition to protection from secondhand smoke exposure, studies indicate that smoke-free homes and workplaces encourage smokers to quit and reduce the number of cigarettes they consume per day.

- The percentage of homes that are voluntarily smoke-free has been rising. Between 2010 and 2011, 83 percent of adults reported they lived in a home where smoking indoors was not allowed, a 93 percent increase from 1992 and 1993, when 43 percent of people reported living in a smoke-free home.

- Smoke-free homes, however, are more common among people with higher levels of education (throughout all racial and ethnic groups) and in states with lower rates of adult smokers.

- The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development has mandated that all public housing agencies adopt a smoke-free policy by July 31, 2018. The policies must prohibit the use of combustible tobacco products in all indoor areas, living units and office units — and within 25 feet of these areas.

SMOKING IN VEHICLES

- Smoking inside vehicles can pose an even greater danger to nonsmokers because concentrations of secondhand smoke are often higher in vehicles than inside homes and bars.

- More than 8 percent (8.2 percent) of nonsmokers were exposed to secondhand smoke in a vehicle within the previous seven days.

- Nonsmokers exposed to secondhand smoke in cars are at an increased risk of cancer.

- From 2013 to 2014, 79.5 percent of adults had a smoke-free vehicle rule.

SMOKING IN THE WORKPLACE

- The surgeon general has concluded that smoke-free workplace policies are the only effective means to eliminate secondhand smoke exposure in the workplace. Separating smokers from nonsmokers, cleaning the air and ventilating buildings does not effectively eliminate exposure. Clean indoor air laws in workplaces reduce nonsmokers’ secondhand smoke exposure by 28 percent.

- Smoking bans in the workplace and in public venues inspire similar voluntary policies in homes.

- Blue-collar workers are more likely to be exposed to secondhand smoke at work.

E-CIGARETTES

- The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine concluded that e-cigarette use raises concentrations of airborne particulate matter and nicotine found indoors.

Thirdhand smoke

- Thirdhand smoke is a relatively new concept that denotes the persisting particulate matter that becomes embedded in environments exposed to cigarette smoke, even after the smoke has cleared from the air.

- Some researchers have surveyed indoor environments exposed to secondhand smoke and found multiple compounds lingering on furniture and other surfaces, such as nicotine and even carcinogenic nitrosamines.

- Additional research is needed on THS to understand the full breadth of potential health effects — especially for infants who are likely to place their mouths on objects in their environment, leading to oral exposures of THS compounds.

The Impact of Secondhand Smoke

Due to the high number of adult and infant deaths each year resulting from secondhand smoke exposure, the surgeon general concluded that there is no safe level of exposure to secondhand smoke.

INFANTS AND CHILDREN

- Maternal smoking during pregnancy and exposure to secondhand smoke in infancy increases the risk of sudden infant death syndrome and contributes to low birth weight, a leading cause of infant mortality.

- Secondhand smoke can cause lower respiratory illnesses (including pneumonia and bronchitis) and persistent adverse effects in lung function during childhood. It can make children’s asthma symptoms more severe, leading to more symptomatic days and increased use of health care services, including hospitalizations.

- Children with asthma who are exposed to secondhand smoke are more likely to have compounding health conditions such as obesity and severe asthma. They are also less likely to visit a health care professional.

- Recent research suggests a connection between secondhand smoke exposure in children and adolescents and an increased risk of developing mental health issues, such as major depressive disorder.

ADULTS

- Secondhand smoke exposure among nonsmokers is responsible for an estimated 7,300 lung cancer deaths and 34,000 cardiovascular disease deaths annually.

- Exposure to secondhand smoke can increase the risk of cardiovascular disease by 25 to 30 percent and the risk of lung cancer by 20 to 30 percent in nonsmokers. Secondhand smoke increases the risk of stroke in nonsmokers by an estimated 20 to 30 percent.

- Deaths caused by secondhand smoke have a disproportionate impact on African-Americans and Hispanics.

- Deaths attributed to secondhand smoke cause $6.6 billion in loss of productivity per year.

Policy in the U.S.

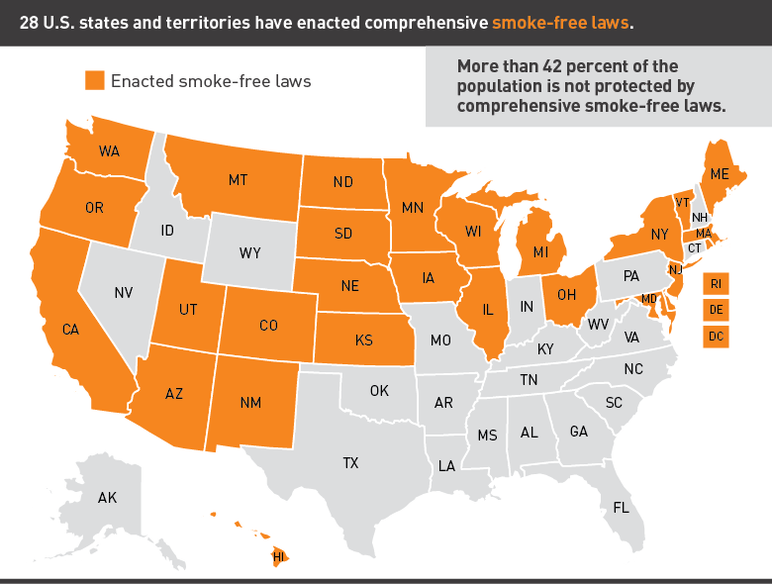

- Although 28 U.S. states and territories have enacted comprehensive smoke-free laws, disparities exist due to gaps in coverage, particularly in southern states and in places where state laws pre-empt local smoking restrictions. More than 42 percent of the population is not protected by comprehensive smoke-free laws.

- Lower-income communities are less likely to be protected by smoke-free laws.

- Many multi-unit housing communities have begun to implement smoke-free policies to protect residents from secondhand smoke, which can infiltrate homes from neighboring units.

- The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development is requiring all public housing agencies to enact a smoke-free policy by July 31, 2018.

Action Needed: Secondhand smoke

Eliminating secondhand smoke by enacting smoke-free protections is necessary to reduce the number of deaths, illnesses and losses of productivity that result from exposure each year.

- States and localities should pass comprehensive clean indoor air measures that prohibit smoking in all workplaces and public facilities, including restaurants, bars and casinos, to provide protection to all people against the serious dangers of secondhand smoke.

- Most e-cigarettes and other electronic nicotine delivery systems emit many potentially toxic substances and should be included in clean indoor air laws. While vapor from such devices is substantially less harmful than smoke from combustible tobacco, there is not enough evidence on the health impact of the potentially toxic substances in secondhand vapor to justify an exemption in the law.

- States and localities should enact further smoke-free restrictions in community settings, such as building entrances, restaurant patios, strip malls, parks and bus stops, to reduce secondhand smoke exposure.

- States and localities should also pass laws making multi-unit housing, such as apartments and condominiums, smoke-free so that secondhand smoke does not infiltrate the units of nonsmokers.